Housing and Economic Research

Original research and analysis on housing trends, the economy and the mortgage market

Economic, Housing and Mortgage Market Outlook – January 2025

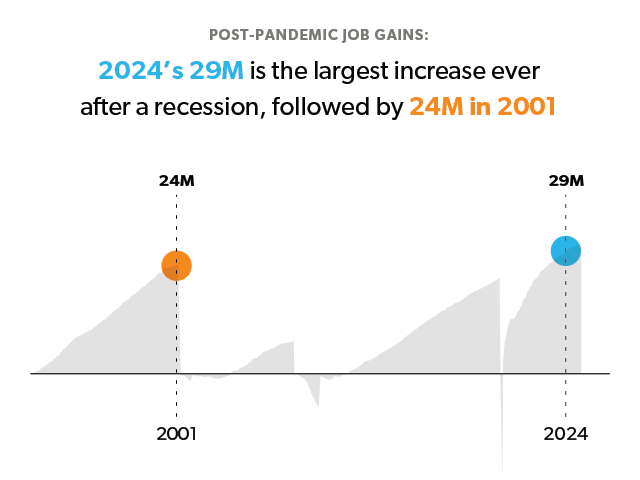

The U.S. economy grew at a stronger pace than initially estimated in the third quarter of 2024 while the labor market remains resilient.

Read MoreEconomic, Housing and Mortgage Market Outlook – January 2025

-

Outlook | December 20, 2024

Economic, Housing and Mortgage Market Outlook – December 2024 | Spotlight: Homeowner vs. Renter Spending

The U.S. economy remains robust with strong Q3 growth driven by consumer spending. More

-

Outlook | November 26, 2024

Economic, Housing and Mortgage Market Outlook – November 2024 | Spotlight: Housing Supply

The U.S. economy remains resilient with strong Q3 growth even as the labor market moderates. More

-

Research Note | November 12, 2024

The Decline in Relative Housing Affordability and the Impact on Homebuyer Search Behavior

In this analysis, we use actual, detailed transaction data on rents, home prices, and mortgage payments for individual homes and borrowers to produce a new relative affordability measure. More

-

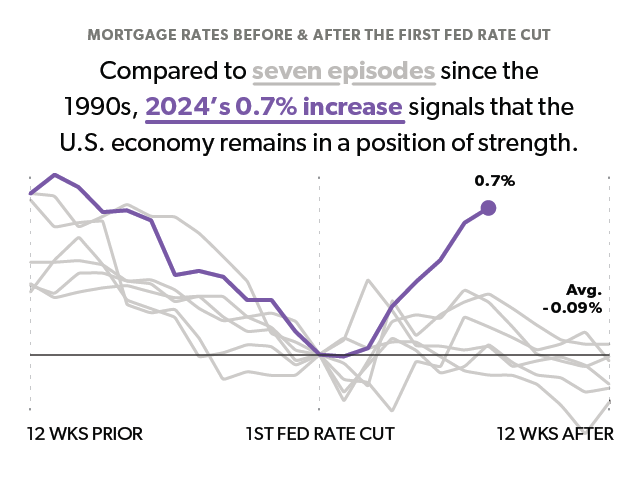

Outlook | October 18, 2024

Economic, Housing and Mortgage Market Outlook – October 2024 | Spotlight: First-Time Homebuyers

The U.S. economy remains strong with upward revisions to GDP growth as well as job growth. More

-

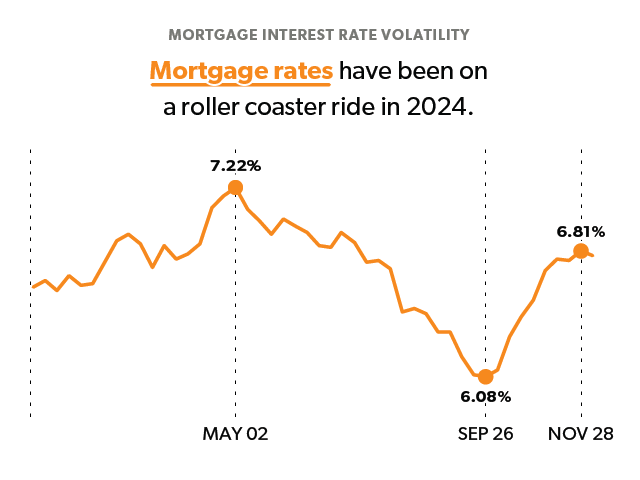

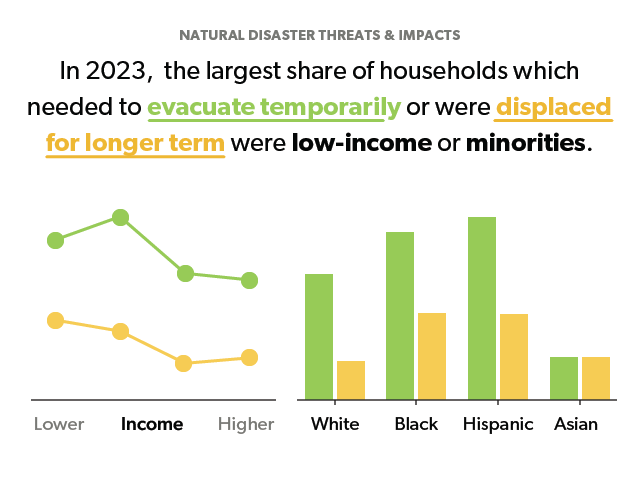

Outlook | September 23, 2024

Economic, Housing and Mortgage Market Outlook – September 2024 | Spotlight: Natural Disaster Threat

The U.S. economy continues to expand but shows signs of slowing, which are consistent with a soft landing. More

-

Outlook | August 20, 2024

Economic, Housing and Mortgage Market Outlook – August 2024 | Spotlight: Refinance Trends

The U.S. economy continues to remain strong as shown in Q2 2024 GDP growth, but some signs of cooling have emerged in the labor market. More